It’s good to have relationships with places. When we go somewhere over and over again, we get to know it intimately, the way we do a loved one. We notice how it’s changed and ways it’s remained the same. We see ourselves in the context of the place, and how we’ve changed, too. Familiar places become benchmarks in our lives, a way to measure time, anchors in an ever-shifting world.

Last weekend we spent four days rafting the San Juan River in southeastern Utah. We’ve floated this stretch at least a dozen times since we took Pippa on her first river trip, in 2009, when she was 10 months old. We’ve run the river in spring at high water, during peak run-off, and on 100-degree days in early June. We’ve rafted with nursing infants, with car seats and Pack ‘n Plays. We’ve zip-tied our tent shut to prevent wayward toddlers from wandering out at night. We’ve gone with big groups and small, in turbulent times and fairer weather. We've lounged around on lazy layover days and paddled hard to make miles before the wind came up.

If I’ve learned anything in all those years, it's that no two river trips are ever the same.

This was the latest we’ve ever rafted the San Juan, but the warm days and clear skies felt more like August than October. Except for our group of 25, the occasional jet streaking overhead, and two ultralights buzzing the rim like birds, we saw no sign of humans for four days—an eerie, unprecedented solitude. It seemed as though we’d found the last peaceful place on earth, unplugged from the turmoil and noise of the world.

We all agreed that given the current state of affairs, absolutely anything could be happening in the real world while we paddled downstream, blissfully unaware. “The river is the real world, Mom,” Pippa reminded me. She was right of course. The limestone walls shot up 500 feet, streaked with desert varnish and strewn with boulders stalled in mid-fall. We slept under a billion bright stars, blinking down on us like lost spirits and paddled beside a herd of bighorn sheep, clattering sure-footedly along the river’s edge. Friends played guitar by firelight and we all sang along. We whittled tiny hearts out of sand. What could be more real than this?

Still, there was something uneasy in the air—not in the canyon but beyond it, an uncertainty pressing in. We’d all heard stories of friends who’d been out of touch on a river during 9/11 or other global events, only to emerge to find life irrevocably altered. This is the beauty of canyons, and why we need them: For a little while, they hold us in and the world out.

It always takes a day or two to settle into a river trip. We’re so accustomed to moving through life at our own pace, but in a canyon you have to move with the water. There’s no point resisting; you have to surrender to the river to truly arrive. On the third morning I woke to the whirling white noise of a rapid just upstream. Something had shifted, lifted. Lying in my sleeping bag, watching the first rays of sun graze the top of the canyon wall, I realized the source of my solace: The canyon was older than any of us. It had weathered everything, and its walls were still standing. Rocks fell and the river flooded, new channels were carved and others abandoned. Sandbars were built up and washed away. But the canyon remained.

I thought about a headline I'd seen in the newspaper the morning we left for the river: “Study Shows It’s Too Late to Stop Climate Change.” It was breakfast time; I felt ill. I couldn’t face the story, but nor could I stop thinking about it. I’d been carrying it with me downstream all this time.

The canyon didn’t change this story. Realistically, it wouldn’t change anything. The news cycle could be blowing up in the so-called real world and we wouldn’t know. What changed in the canyon was the scale of time. It was both shorter and longer; faster and slower. A flash flood could rip through in seconds. We’d seen the debris from summer storms: tree trunks flung up on boulders 50 feet above the water line, brush tangled into enormous knots like an Andy Goldsworthy exhibition, giant slabs of drying mud flaking and cracking into strange, accidental patterns at the water’s edge. And yet, the walls were 300 million years old. They might stand another million years, long after the river runs dry and we humans are gone.

Impermanence is the first teaching of Zen. Change is constant; nothing ever stays the same. Even very old places don’t last. Resist the shifts, and we suffer; learn to flow with them and we’re free. Rivers teach us how to hold both truths at once.

When we got out of the canyon and back into cell service, nothing of note had happened and also a million things had. It drizzled and there was a chill in the air; all our gear was covered in mud. We’d be scrubbing it off for days. Summer had shifted over to fall. And yet life kept keeping on. The news was weirder and darker than when we’d left, but we were brighter. We’d found consolation in the canyon, in each other, and in the ever-shifting current of water and time.

What happens next is anyone’s guess. But the canyon reminds us that if we’re strong like the walls and agile like the water, we’ll handle whatever comes our way.

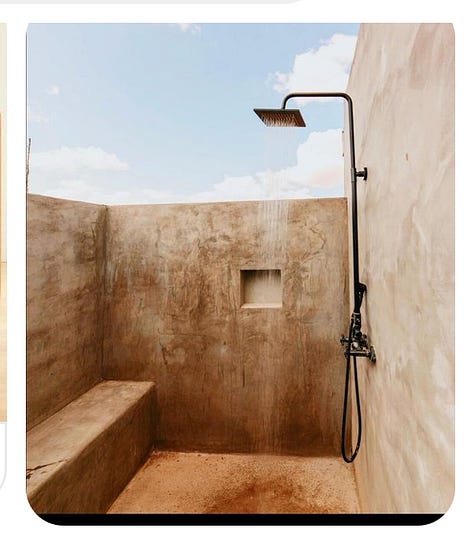

Are you ready to bring more joy, ease, and inspiration into your life in 2025? Join us for Desert Flow Camp, Feb 12-16, at Willow House in Big Bend, Far West Texas. Guided writing, trail running, yoga, hiking, solitude, silence, friendship, mentorship, dazzlingly dark skies, stylish digs, and delicious food, and daily flow practices you can do anywhwere, anytime. Flow Camp is a magical weekend of adventure, creativity, + community that will transform the way you move through the world. Coed.

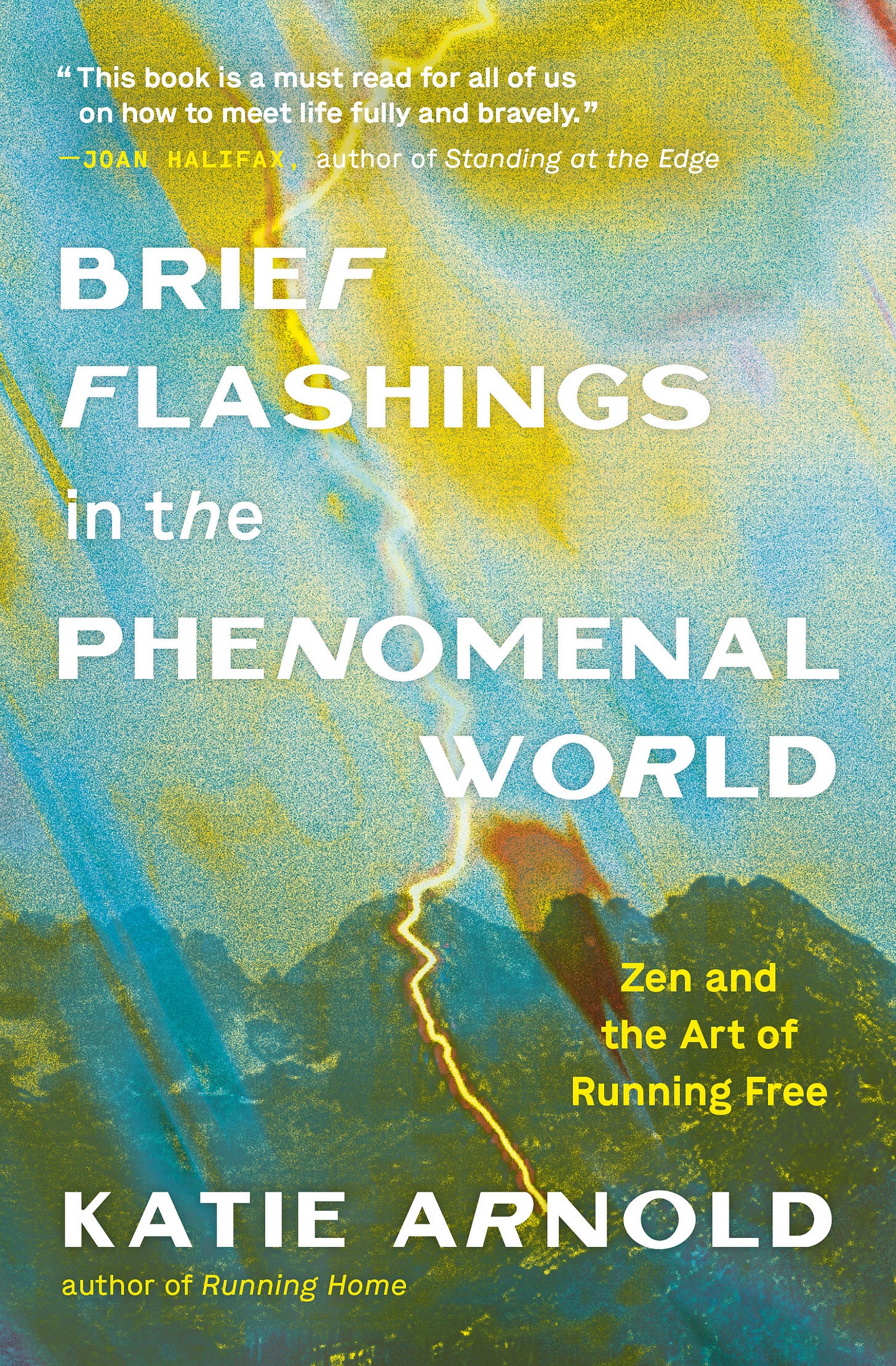

you ARE the flashings,

xo katie

Love those sand hearts!! Will you share with me, with 2 sentences aboutnthem, and the location and date?! :)