It’s important to do things you're not good at, not so you can get better at doing them but so you can be OK with being so-so. There are lots of things I’m not good at. Following a recipe is one of them; remembering things I learned in high school math, golf. But I’m not talking about the sorts of things that you’re not particularly fond of, that perhaps you don’t even like.

No, I’m talking about doing something you’re not good at that you actually, genuinely enjoy. When you do, you begin to associate process with pleasure, or to put it another way, to unhook practice from success. You remember what it is to love something for the pure act of doing it, not for the result.

About two months ago, I started teaching myself to slack line. My daughter had gotten one for her birthday, and she and her friend strung the 30-foot webbing up between two stunted elm trees in the arroyo below our house. The sandy wash drains the crumbly ridges and badlands that surround our property, less than a mile from the Santa Fe Plaza. Most of the time the arroyo is dry, but during big storms, it gushes with silty, brown run-off. Afterwards, when the mud has finally dried, the arroyo is swept clear of debris, the sand fine and soft and almost pristine. A beach in the desert.

In other words, it’s a perfect place to learn to wobble along a thin line of webbing a foot off the ground. Or more precisely, a perfect place to fall.

I didn’t have any grand plans for slack lining. At first, I was just curious to see the line and how they’d rigged it. We’d had one years ago that we never used, probably because it spanned a bristly, inhospitable patch of cacti-studded dirt, the only flat ground on our property.

They’d rigged this line with a top line about seven feet above the walking line, for balance. Tentatively I climbed on and held the top line. Instinctively, I locked my knees, bracing against the fall. My stiff, straight legs gyrated wildly below me, causing both lines, and my arms, to buck and sway with cartoonish exaggeration. My daughter howled with laughter. I gripped the top line and took a few steps on unsteady legs, staring down at my bare feet splayed precariously on the webbing. I could barely take two steps while holding on, let alone imagine walking its length with no hands.

Despite this—or likely because of this—I was intrigued. The next morning, I wandered down with my coffee to try again. The arroyo runs almost due east to west, so the slack line gets both the morning and evening sun. Though there are a few houses above the arroyo to the south of ours, the line is tucked just out of view of all of them. It feels like a private, secret oasis, shaded from sun early in the day, bathed in sunset glow before dinner.

I went down that evening, too. I liked having some place close by to go when I needed a break from writing, or in the late afternoons, when I was waiting for the girls to come home from schoo. I liked having a small project that challenged both my body and brain at the same time, and the satisfaction I got from trying something new, and difficult, without guarantee of success or even mediocrity.

I walked the line holding on with both hands, and then just one hand, for a week. The slack line was becoming my morning practice, but I couldn’t imagine taking steps without holding on. One day it occurred to me to look on YouTube. It turns out, I discovered, that rather than trying to walk on the line right away, you must first learn to balance, on one foot then the other. Try to make it to the count of 100, the man on the video instructed. I got to seven. Keep your knees slightly bent and your center of gravity lower, he went on; don’t stretch your arms out to the side like a circus tight-rope walker holding a stick, but up into the air. Stare at the far end of the line, not down at your feet.

Every day, and often twice a day, I went down to the slack line. Something unexpectedly wonderful was happening. I could feel my body getting stronger down the whole chain, from my shoulders to my feet, especially on my left side, long compromised by two surgeries and a broken ankle. My left knee, which used to balk at lateral movement and cave inward a little, looked straighter and more aligned from supporting my body weight on a wiggy line.

It was just a wild hunch, based on nothing but instinct and hope, but I thought that if I kept practicing, slack lining would reconnect my body to itself and to my mind, and put me back together stronger than I’d ever been. Maybe slack lining would help me return to running ultra distances.

I didn’t need to fact-check this. I felt, deep down, that it was true, even if it was only in my mind. Soon I was taking a few steps unassisted. I kept walking, day in and out, because I loved how I felt when I was in the arroyo, taking one step and then two with no hands. Falling off and getting back on, no longer afraid of falling. Turning up the music on my phone and disappearing, for a few minutes, into the balancing act. Holdin the top line if I needed to, sometimes forgetting and looking at my feet. Hopping off to throw a stick for my dog Banks.

It’s not that I don’t aspire to get better at slack lining. I do. A few weeks ago, I came up to the house and proudly announced to Steve that I’d taken three steps without falling. “You’re ready to move to Moab,” he proclaimed drily. Moab’s where all the dirtbag rock climbers slack line on their rest days to improve their balance and core strength.

I laughed. Progress feels good. It’s measurable and pleasing. But is it essential to my enjoyment of slack lining? Not really. Do I have any illusions of grandeur? Absolutely not. What I love is having a place to go, a skill to practice, a morning routine, the freedom of no one watching, or caring, cool sand beneath my bare feet, climbing onto the line, and feeling my body come alive with confidence and concentration.

I know this feeling. I remember it from childhood, and maybe you do, too. The simple joy of applying yourself to something with total presence and pleasure, without pressure to perform isn’t work. It’s play.

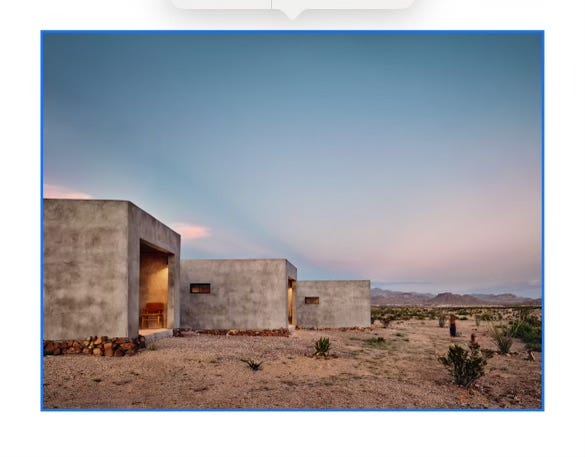

It’s official! Save the date for Desert Flow Camp, February 12-16 in far West Texas, just outside of Big Bend National Park. Four nights, five days. Dark skies, uncrowded trails, desert inspo, friends + oh so much flow. This one will sell out early, so click the registration link below to see if Flow Camp is right for you. The ruggedly beautiful West Texas landscape is a perfect backdrop for exploring our unbounded imaginations, and if you like your creature comforts close to nature, you’ll love the stylish and souful Willow House. We’ll be writing on love, loss, desire in all its forms, and the stories we keep hidden and those we long to tell. COED!

Come for Desert Flow Camp + stay a few extra days in the artsy outpost Marfa.

so hope you’ll join us!

xo Katie

Katie- I re-read this a few times like I often do with pages from your books. I think it may make its way into your next book... And the whole experience you describe resonated with me. I have zero talent or ability in drawing. Always self-conscious about the product of my drawing all these years, I steered clear, but I recently attended a nature drawing class on a whim. After all these years, I missed drawing and I was able to just let my colored pencil flow without any thought of my outcome. Great lesson to take back to my writing and the rest of my life. Thanks.

Love this so much, Katie. I can feel the positive energy radiating from your practice all the way in the green mountains. ❤️