This past week marked the 14th year since my father died, and I got new glasses. New-old glasses. Dad’s glasses.

I found the frames in his nightstand after he died, and I asked my stepmother if I could have them. She said yes, of course, and I carried them home in my suitcase, along with some of his notebooks and other small mementos. The wide tortoise-shell frames had lenses so thick they made the world wobble when I looked though them. This was his signature look. Dad wore glasses like this for much of his life; they made him look both brainy and sensitive. I stuck them into a drawer in my writing loft, took them out from time to time. Eventually, forgot.

Recently, I remembered Dad’s glasses. My 20/20 vision was getting dicey after dark, and I needed to get my prescription checked. I’d gotten my only pair of glasses in 1993, during my last year of college, after staring at the blackboard for so long my eyes began to tear. The frames were a dark plumb in color, with oval lenses as small as walnuts. I rarely, if ever, wore them.

At my appointment, the optometrist was impressed. “Your vision has barely changed,” he said. “That’s what we like to see.”

My father, on the other hand, had been legally blind. I wondered when he’d last worn the glasses that were now tucked carefully into my bag, and what he’d looked at. If I looked closely, could I see what he saw? In his later years, he’d sported a more subtle grey wire-rimmed pair, with bifocals, but when I pictured him in my mind, he was always wearing the round tortoise shells and carrying his camera, a double lens through which he viewed the world.

When it came time to pick out new frames, I pulled Dad’s glasses shyly from my lap and set them on the table in front of me. “Do you ever use—I mean, is it possible to use…” I was having trouble with the words. “Old frames? These were my dad’s.” For clarity, I added, “He’s dead.”

The optometrist associate’s face lit up and softened at the same time. “Oh yes, we do this a lot.” He reached for them gently. “Wow, look at that. They’re actually glass.” And for a moment I felt proud of my dad for having had such terrible vision that he’d had such marvelous glasses.

A couple weeks later, I got a text that my frames were ready. It was, coincidentally, Dad’s going-away day. I don’t like to call it an anniversary, which sounds celebratory and alive, which he wasn’t anymore. But he wasn’t forgotten, nor would he ever be. It was his remembrance day. Yes, that’s better.

The man at the glasses store had me try on my new-old frames. Then he handed me Dad’s thick, curved soda-bottle lenses, wrapped carefully in a protective sleeve. I was so happy he’d saved them. I liked knowing I could pull them out at any time and see the world through Dad’s eyes, even though his prescription was so strong that, looking through them, I couldn’t see anything.

More than anything, this is what Dad had taught me: how to see, pay attention, notice all the moments, big and small, the brief flashings in the phenomenal world. In his famous 1836 essay, “Nature,” Ralph Waldo Emerson described this way of seeing clearly, observing without judging, as a “transparent eyeball”— when the looker disappears and becomes, simply, looking:

“I become a transparent eyeball. I am nothing; I see all. The currents of Universal Being circulate through me.”

Rereading these lines now, thirty years after I first read them in college, I hear the echo of old Zen texts, though none had yet been translated into English at the time of Emerson’s writing. The eyeball in Zen represents insight, perceiving the true nature of being, without interpretation, bias, or analysis. Just seeing. And I think about how this is my highest aim in writing: to embody a moment rather than explain it; to close the gap between our idea of something and the thing itself. Its essence.

Like a photograph.

I drove home wearing Dad’s transparent eyeballs, even though it was broad daylight. They were nice. the nerdy sturdiness of the frames felt like him and looked like a cooler version of the trendy readers everyone’s wearing right now. I caught a glimpse of myself in the rearview mirror, and Dad smiled back. The truth was, I don’t need his glasses to see. I already know how.

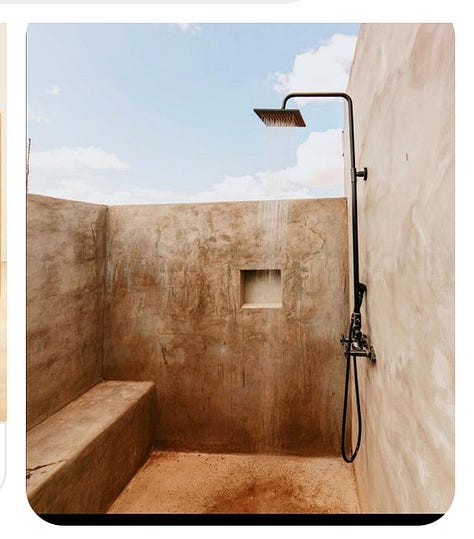

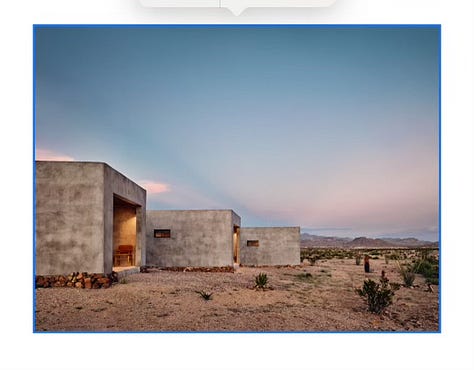

Where do you see yourself in 2025? Join us at Desert Flow Camp, February 12-16 in the wilds of West Texas to practice new ways of seeing, running, writing, and being. At this coed running and writing retreat, we’ll connect with our inner creativity, in art, sport and life, and explore pleasurable habits designed to bring more ease, momentum, and energy into everything we do. If you’re ready to deepen your relationship with running, writing, and seeing, you do not want to miss this! Exceptional Big Bend trail running and hiking out the door, yoga, meditation, guided writing and mentorship, inspiration, and nourishing food and friendships. Join us in the flow!

From $2750 pp (shared King) - $3650 (private King casita)

.Registration and info at QR code and link below!

See you in the flow!

xx katie

Katie- I love this entry of your continued grief journey and relationship with your dad. I love so much about it, and how it flows back to your dad teaching you to see! Simple and brilliant at the same time.( Another wise piece for your next book-I can tell....) P.S. You look great in the glasses just like him!

thank you so much Robin. this means so much to me because it's a subject so close to my heart and becaus, for the last couple of weeks I've felt too scattered to write, and wondered why and what it's for--so to hear this struck a chord with you is heartening indeed. much love! how's your writing! I'd love to hear....xox